Major points:

- A scientific study by the Neatic team examined over 1,800 foods to define ingredients that effectively identify ultra-processed foods (UPFs).

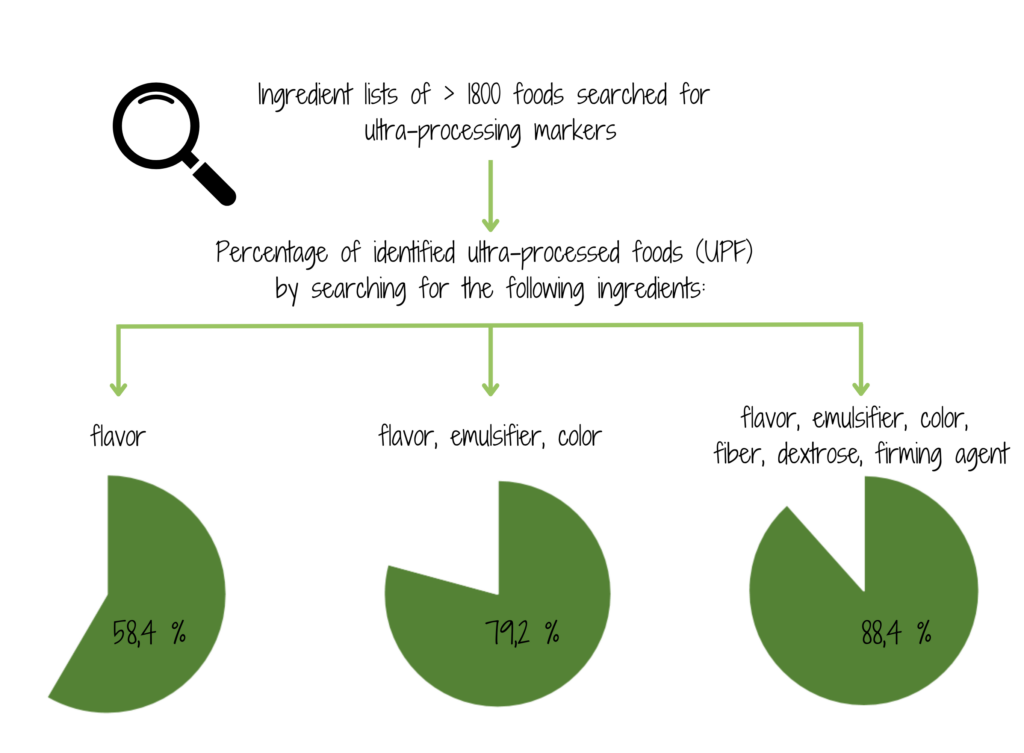

- The term “flavor” alone correctly identified more than half (58.4%) of UPFs. This detection rate increased to nearly 9 out of 10 (88.4%) UPFs when the ingredients list were also searched for emulsifier, color, fiber, dextrose, and firming agent.

- This study demonstrates that by following Neatic Principle No. 1 (avoid flavors), consumers can correctly identify more than half of all UPFs, providing a simple method to avoid them.

What are ultra-processed foods and what impact do they have?

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are highly processed products manufactured through multiple industrial processes and the use of additives. In the NOVA classification, which categorizes foods into four groups based on their degree of processing, UPFs fall into Group 4. They can be recognized by markers of ultra-processing (MUPs) which can be found in the ingredient list. Studies have shown that consuming UPFs is associated with various diseases and increased mortality.

What does the study investigate?

The NOVA classification describes more than 100 MUPs. A food is considered a UPF if it contains at least one of these MUPs. To help consumers to identify UPFs more easily, the Neatic team conducted a study to determine which combinations of MUPs can detect the majority of UPFs.

The Neatic team analyzed the ingredients lists of 1,836 typical foods from the British market, sourced from the supermarkets Tesco and Sainsbury’s, to check for the presence of various MUPs.

What did the study find?

Out of the 1,836 foods analyzed, 990 (53.9%) contained at least one MUP and were classified as UPFs. The most common MUP was added flavor, found in 578 products (58.4% of all UPFs), followed by emulsifier in 353 products (35.7%), and color in 262 products (26.5%).

By considering the combination of added flavor and emulsifier, 72.7% of all UPFs could be identified. Including color as a third marker increased the identification rate to 79.2%. The most effective four-marker combination (added flavor, emulsifier, color, and fiber) identified 82.8% of UPFs. Adding dextrose as a fifth marker increased this to 85.8%, and including firming agent as a sixth marker raised the identification rate to 88.4%.

What is the conclusion of the study?

The study’s findings allow consumers to find the optimal balance between the number of MUPs to remember and the proportion of correctly identified UPFs. By checking for six MUPs in ingredients lists, nearly 9 out of 10 UPFs can be successfully identified, enabling healthier choices by avoiding UPFs linked to various health issues.

The study also shows that by following Neatic Principle No. 1 (avoid flavors), nearly 6 out of 10 UPFs can be correctly identified, offering a simple way to recognize and avoid UPFs.

Bibliography

Bonaccio, Marialaura; Costanzo, Simona; Di Castelnuovo, Augusto; Persichillo, Mariarosaria; Magnacca, Sara; Curtis, Amalia de; Cerletti, Chiara; Donati, Maria Benedetta; Gaetano, Giovanni de; Iacoviello, Licia (2022): Ultra-processed food intake and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in individuals with cardiovascular disease: the Moli-sani Study. In: Eur Heart J 43 (3), pp. 213-224. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab783 .

Li, Huiping; Li, Shu; Yang, Hongxi; Zhang, Yuan; Zhang, Shunming; Ma, Yue; Hou, Yabing; Zhang, Xinyu; Niu, Kaijun; Borné, Yan; Wang, Yaogang (2022): Association of Ultraprocessed Food Consumption With Risk of Dementia. In: Neurology 99 (10), e1056-e1066. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000200871 .

Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Cannon, Geoffrey; Levy, Renata Bertazzi; Moubarac, Jean-Claude; Louzada, Maria Lc; Rauber, Fernanda; Khandpur, Neha; Cediel, Gustavo; Neri, Daniela; Martinez-Steele, Euridice; Baraldi, Larissa G.; Jaime, Patricia C. (2019): Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. In: Public Health Nutr 22 (5), pp. 936-941. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762.

Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Cannon, Geoffrey; Moubarac, Jean-Claude; Levy, Renata Bertazzi; Louzada, Maria Laura C.; Jaime, Patrícia Constante (2017): The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. In: Public Health Nutr 21 (1), pp. 5-17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000234.

Narula, Neeraj; Wong, Emily C. L.; Dehghan, Mahshid; Mente, Andrew; Rangarajan, Sumathy; Lanas, Fernando; Lopez-Jaramillo, Patricio; Rohatgi, Priyanka; Lakshmi, P. V. M.; Varma, Ravi Prasad; Orlandini, Andres; Avezum, Alvaro; Wielgosz, Andreas; Poirier, Paul; Almadi, Majid A. Altuntas, Yuksel; Ng, Kien Keat; Chifamba, Jephat; Yeates, Karen; Puoane, Thandi; Khatib, Rasha; Yusuf, Rita; Boström, Kristina Bengtsson; Zatonska, Katarzyna; Iqbal, Romaina; Weida, Liu; Yibing, Zhu; Sidong, Li; Dans, Antonio; Yusufali, Afzalhussein; Mohammadifard, Noushin; Marshall, John K. ; Moayyedi, Paul; Reinisch, Walter; Yusuf, Salim (2021): Association of ultra-processed food intake with risk of inflammatory bowel disease: prospective cohort study. In: BMJ 374, n1554. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1554.

Neumann, Nathalie Judith; Eichner, Gerrit; Fasshauer, Mathias (2023): Flavor, emulsifiers and color are the most frequent markers to detect food ultra-processing in a UK food market analysis. In: Public Health Nut 26 (12), pp.3303-3310. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980023002185

Rauber, Fernanda; Chang, Kiara; Vamos, Eszter P.; da Costa Louzada, Maria Laura; Monteiro, Carlos Augusto; Millett, Christopher; Levy, Renata Bertazzi (2021): Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of obesity: a prospective cohort study of UK Biobank. In: Eur J Nutr 60 (4), S. 2169-2180. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02367-1.