Major points

- Intermittent energy restriction involves alternating between periods where normal eating is allowed and fasting periods, which leads to a reduced overall calorie intake.

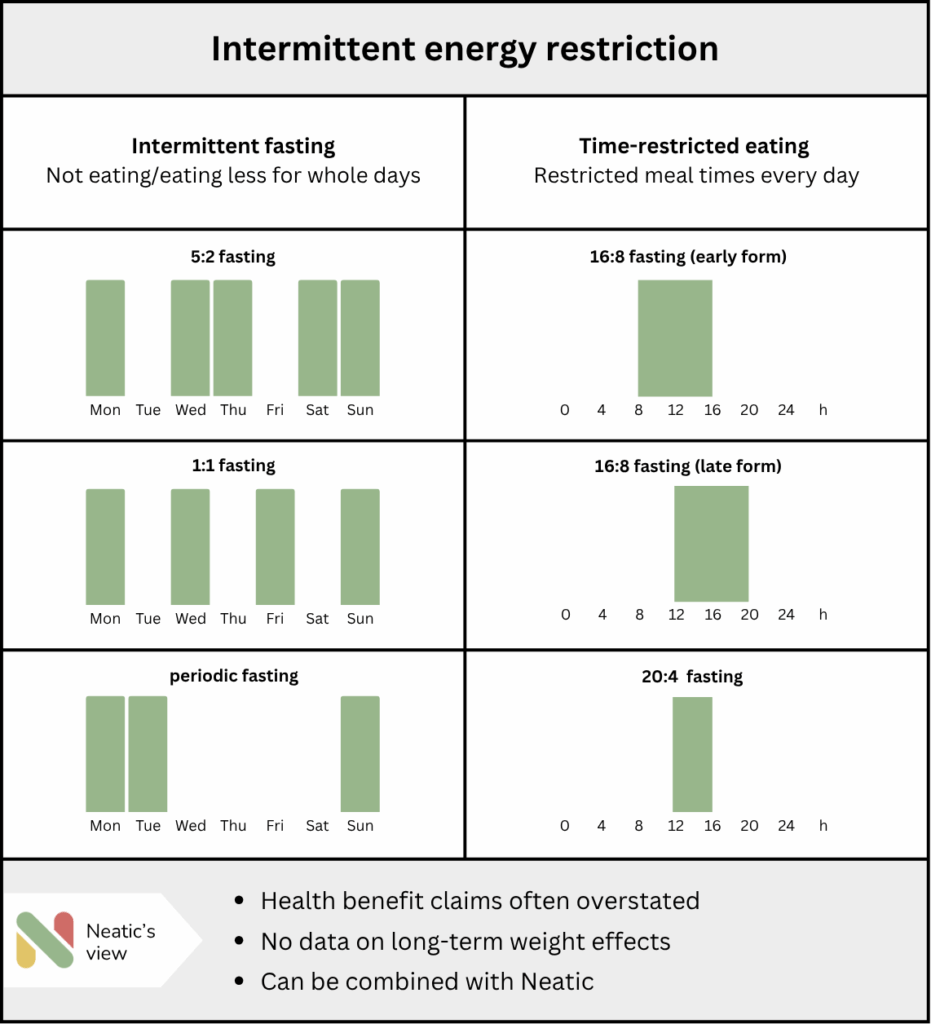

- There are two main types of intermittent energy restriction: intermittent fasting (IMF), where fasting occurs on whole days, and time-restricted eating (TRE), where daily eating times are significantly limited.

- There is currently no convincing evidence that intermittent energy restriction offers better health effects compared to regular diets. However, intermittent energy restriction can certainly be combined with Neatic.

What is intermittent energy restriction?

The term “intermittent energy restriction” is self-explanatory. “Intermittent” refers to a time period, and “energy restriction” means eating nothing or significantly less than usual. Therefore, “intermittent energy restriction” means eating nothing or significantly less within a defined period of time. This results in a reduced total calorie intake.

Is intermittent energy restriction always the same?

No! There are two main types, each with different subtypes: intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating.

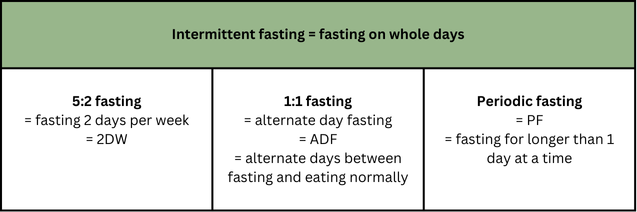

1. Intermittent fasting (= IMF)

This form involves fasting for entire days. The following subtypes are particularly popular:

- 5:2 fasting: You eat normally for five days a week and fast for two days. For example, you might fast completely on Tuesdays and Fridays, while eating normally on the other five days. Sometimes, fasting days do not mean total abstinence from food, but allow up to 500 kilocalories, which could be the equivalent of two cheese rolls or half a frozen pizza.

- 1:1 fasting: Days of normal eating alternate with fasting days. For example, you would eat normally on Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday, while fasting on Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday, and the next Monday. In the modified version, you would not completely refrain from food, but limit your calorie intake to around 500 kilocalories on fasting days.

- Periodic fasting: Fasting lasts for more than one consecutive day. For example, you might fast for a whole week or severely restrict your calorie intake during this period. This type of fasting is also common in certain religious practices.

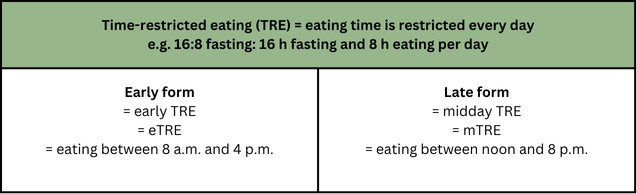

2. Time-restricted eating (TRE)

In this type, you eat every day, but the eating period is limited. The most popular form is 16:8 fasting, where you fast for 16 hours a day and can eat during an 8-hour window. Depending on when you start eating, there are two types of 16:8 fasting:

- Early TRE (eTRE): You start eating early, for example at 8 a.m., and can eat until 4 p.m.. From 4 p.m. until the next day at 8 a.m. you fast.

- Midday TRE (mTRE): You start eating around noon, and can eat until 8 p.m.. From 8 p.m. until noon the next day, you fast.

There are more extreme versions, such as 20:4 fasting, where you fast for 20 hours and eat during a 4-hour window. However, these extreme methods are difficult to maintain for most people.

Why do people practice intermittent energy restriction and what does research say?

It is often claimed that intermittent energy restriction helps shed pounds, improves metabolism, prevents cardiovascular diseases, reduces inflammation, boosts fitness, and extends life. However, many of these claims are either unproven or insufficiently supported by scientific studies.

When studies do exist, they often suffer from several common issues:

- The number of participants is too small, making the results less reliable.

- The follow-up period is too short to assess the risk of the yo-yo effect.

- A high dropout rate, where participants who struggled with fasting may have left the study, potentially skewing the results.

- Different types of intermittent fasting are studied, making comparisons between studies difficult.

- Often, there is no control group with a standard diet, so it is unclear how intermittent fasting compares to regular dieting.

- Conflicts of interest may exist, as some studies investigate products being marketed for sale.

Some of these problems can be mitigated when several studies on intermittent energy restriction are combined in a so-called meta-analysis. Simply put, in a meta-analysis, for example, three different studies with 30, 50, and 70 participants are combined and evaluated using special statistical methods as if it had been one large study with 150 (=30+50+70) participants. In 2022, such a meta-analysis on the effects of intermittent energy restriction on body weight was published. Sixteen studies were included in the main evaluation.

Per study, between 8 and 68 participants took part in intermittent energy restriction, which was carried out between 2 weeks and 6 months. All studies had a control group with a calorie-reduced diet. Weight loss in intermittent energy restriction across the 16 studies ranged between 0.5 kg and 13.9 kg, and in calorie-reduced diets between 1.9 kg and 11.8 kg. Weight loss with intermittent energy restriction was not statistically significantly different compared to a calorie-reduced diet. In addition, there were no statistically significant differences in weight loss between 1:1 fasting, 5:2 fasting, and time-restricted eating. Maintaining intermittent energy restriction became increasingly difficult for participants over time, as is also typical for calorie-reduced diets.

The key results of this meta-analysis were confirmed in two subsequent high-ranking published studies.

In a study by Lin and colleagues, time-restricted eating (mTRE) was compared with a calorie-reduced diet (=25% reduction in calorie intake). Each group included 30 participants who were followed for 12 months. Most participants completed the study successfully. Weight loss after 12 months was 4.6 kg in the time-restricted eating group and 5.4 kg in the calorie-reduced diet group. However, the difference of 0.8 kg between the two groups was not statistically significant. The authors concluded that time-restricted eating over a period of 12 months is not more effective than a calorie-reduced diet.

In another study, Liu and colleagues investigated whether time-restricted eating (eTRE) over 12 months in addition to a calorie-reduced diet (= energy intake between 1200 and 1500 kilocalories per day for women or between 1500 and 1800 kilocalories per day for men) is more effective for weight loss than a calorie-reduced diet alone. In total, 139 participants were equally divided into the two groups, and most participants completed the study successfully. The average weight loss after 12 months was 8.0 kg in the time-restricted eating and calorie-reduced diet group and 6.3 kg in the group with calorie-reduced diet alone. However, the difference of 1.7 kg between the two groups was not statistically significant. The authors concluded that time-restricted eating in addition to a calorie-reduced diet does not offer a significant advantage for weight loss.

What does Neatic recommend concerning intermittent energy restriction?

Many claims about the positive health effects of intermittent energy restriction are exaggerated and not supported by scientific studies. In particular, convincing studies showing that permanent weight loss is possible and that intermittent energy restriction is more effective than calorie-reduced diets are missing.

However, if you would like to try intermittent energy restriction, you can certainly combine it with Neatic.

With intuitive eating, however, there are no time restrictions. If you want to find out more about it, click here.

Bibliography

Elortegui Pascual, Paloma; Rolands, Maryann R.; Eldridge, Alison L.; Kassis, Amira; Mainardi, Fabio; Lê, Kim-Anne; Karagounis, Leonidas G.; Gut, Philipp; Varady, Krista A. (2023): A meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of alternate day fasting, the 5:2 diet, and time-restricted eating for weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring) 31 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1), S. 9–21. DOI: 10.1002/oby.23568.

Lin, Shuhao; Cienfuegos, Sofia; Ezpeleta, Mark; Gabel, Kelsey; Pavlou, Vasiliki; Mulas, Andrea; Chakos, Kaitie; McStay, Mara; Wu, Jackie; Tussing-Humphreys, Lisa; Alexandria, Shaina J.; Sanchez, Julienne; Unterman, Terry; Varady, Krista A. (2023): Time-Restricted Eating Without Calorie Counting for Weight Loss in a Racially Diverse Population : A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med 176 (7), S. 885–895. DOI: 10.7326/M23-0052.

Liu, Deying; Huang, Yan; Huang, Chensihan; Yang, Shunyu; Wei, Xueyun; Zhang, Peizhen; Guo, Dan; Lin, Jiayang; Xu, Bingyan; Li, Changwei; He, Hua; He, Jiang; Liu, Shiqun; Shi, Linna; Xue, Yaoming; Zhang, Huijie (2022): Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss. N Engl J Med 386 (16), S. 1495–1504. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114833.